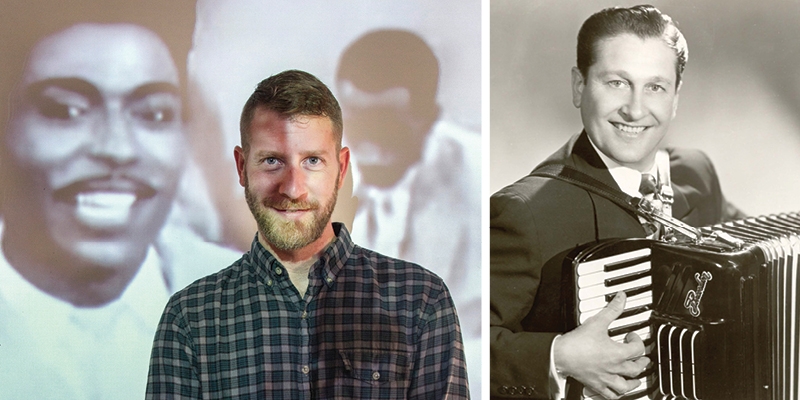

Ben Hudson is a newly-hired Rollins College English professor. His class is in bad taste. Not bad taste as in socks with sandals, gardens with gnomes and prison tattoos. Bad taste as a theme in his writing classes.

It’s a strategy he has used since his days at the University of Georgia, where he taught undergraduates while earning his Ph.D.

He starts by assigning the works of notable arbiters of taste, from ’60’s counterculture firebrand Susan Sontag to Immanel Kant, an influential 18th–century philosopher who argued that our perception of good taste is utterly illogical.

In Kant’s view, when something strikes us as beautiful — a person, a painting, a gorgeous view — our response is purely emotional, so don’t bother arguing with us about it. De gustibus non est disputandum, said the Romans. Or, to quote the aphorism of another era: There’s no accounting for taste.

But Hudson is a southern-boy contrarian at heart. What he really wants his students to understand is that Kant assumed that he and his homies — namely upper-class European males — considered themselves to be the sole judges of taste, good or bad.

Yet, something that’s perceived as distasteful by the powers that be can, in fact, be a good thing — maybe even a revolutionary thing — and certainly something a good writer should investigate. So, Hudson asks students to write about something they dislike — a fad, a movie, a singer.

For inspiration, he has them read essays that celebrate outliers. One example is a rave review of a kitschy Times Square eatery called “Senor Frog” by ordinarily snooty New York Times critic Pete Wells, who applauded the eatery’s artful tackiness in decking out diners in balloon-animal head gear and offering up drinks in suggestively-shaped cups.

On the day I visited Hudson’s classroom, at the end of an Olin Library hallway decorated with posters offering chipper grammatical warnings (“How to Use a Semicolon: The Most Feared Punctuation on Earth!”), he was discussing one of the patron saints of bad taste: John Waters, the puckish filmmaker with a pencil-thin moustache who made underground movies celebrating bizarre behavior and outlandish characters in the early ’70s.

Hudson had assigned his students to watch a somewhat tamer film Waters made later in his career: the 1988 version of Hairspray, starring Ricki Lake, Sonny Bono and Divine.

The story, set in Baltimore in 1962 against the backdrop of the civil rights movement, revolves around a televised dance competition and the backlash it generates against two teenaged contestants. One is overweight, and the other is black, as are the musicians playing the songs to which all the kids — regardless of skin tone — want to dance.

It’s easy enough for anybody who came up in the ’60s to relate to the attitudes evidenced in Hairspray. But in a classroom filled with 19-year-olds who hadn’t yet been born when the movie was released — and for whom the ’60s is ancient history — Hudson’s leading questions engendered long silences and puzzled faces.

So, he provided historical perspective via a black-and-white YouTube video from 1958. A familiar figure — well, familiar to me, anyway — appeared on the screen, his eyes wild, his hair in a towering Pomade pompadour. He stood at a piano, pounding a hotwire beat into its keys and howling:

LUCILLLLEEEE! Please come back where you belong!

I been good to ya baby, please don’t leave me alone!

The flamboyant figure was, of course, Little Richard, of whom John Lennon once said: “If you don’t like rock ’n roll, blame him.”

Lucillllleeee!

I could hardly keep my feet still. After all these years, listening to music that once gave grownups headaches still felt like a guilty pleasure. Surely the classroom door was about to swing open and we were all going to get hauled off to detention.

But then Hudson switched to another video. Same era. Way different music. It was Lawrence Welk, a wunnerful, wunnerful big-band leader with a heavy German accent whose weekly television show featured such catchy songs as “The Beer-Barrel Polka.” The maestro’s music was a Saturday-night staple in my family’s living room — and every bit as exciting as its floral wallpaper.

For just a second there, during Little Richard’s romp, I had felt young again. The sensation was fleeting, thanks to one of Hudson’s students, who squinted at Welk’s image on the screen and had a flash of recognition.

“I know who that is,” she said. “My grandmother still watches him.”

Michael McLeod is a contributing writer for Winter Park Magazine and an adjunct instructor in the English department at Rollins College.