Photographs by Rafael Tongol and Martin Schiff

A few weeks ago, an audience of about 500 people gathered at the Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts to watch miracles materialize on the stage of the Walt Disney Theater.

It wasn’t a magic show, a motivational seminar or a spiritual gathering, though it had something in common with all three.

The annual event, dubbed the Composium, is the capstone of the National Young Composer’s Challenge, conceived by Winter Park inventor/philanthropist Steve Goldman to discover and nurture budding musical genius.

Every year, in what amounts to a classical-music version of a fantasy baseball camp, Goldman brings a half-dozen brilliant teenaged NYCC winners to Orlando, where they hear their five-minute compositions rehearsed, performed and recorded by professional musicians.

This year marked the return of the Orlando Philharmonic Orchestra to the event, along with chamber ensemble musicians from the University of Central Florida faculty. Both groups were under the baton of Christopher Wilkins, the Phil’s former music director and an NYCC mainstay.

Most of the players were at least twice the age of the young composers, several of whom started creating music on their own in grade school.

While the youngsters may have been regarded as anomalies among classmates, teachers and parents, they found themselves among kindred spirits at the Composium. And it’s hard to say who enjoyed the situation more — pros or protégés.

“They’re the miracles of our time,” said violist Melissa Swedberg, one of the Phil musicians who shared the stage with the six selectees. “Their amazing creativity, the sophistication of their music — where does that come from?”

Added Goldman: “These kids are one in a million. More like one in 10 million. A lot of them are already writing at the level of the most advanced adult composers I know of. The level of emotion, the sense of beauty you see from these hyper-talented musicians — it’s something that seems to peak at a young age.”

So, apparently, does a disarming inventiveness. It’s unlikely that a mature composer would have requested the simple but ingenious sound effect prescribed in Paper Man, a winning orchestral score submitted by 17-year-old Harrison Collins of Little Elm, Texas: It called for musicians to hold a sheet of paper in the air and rattle it.

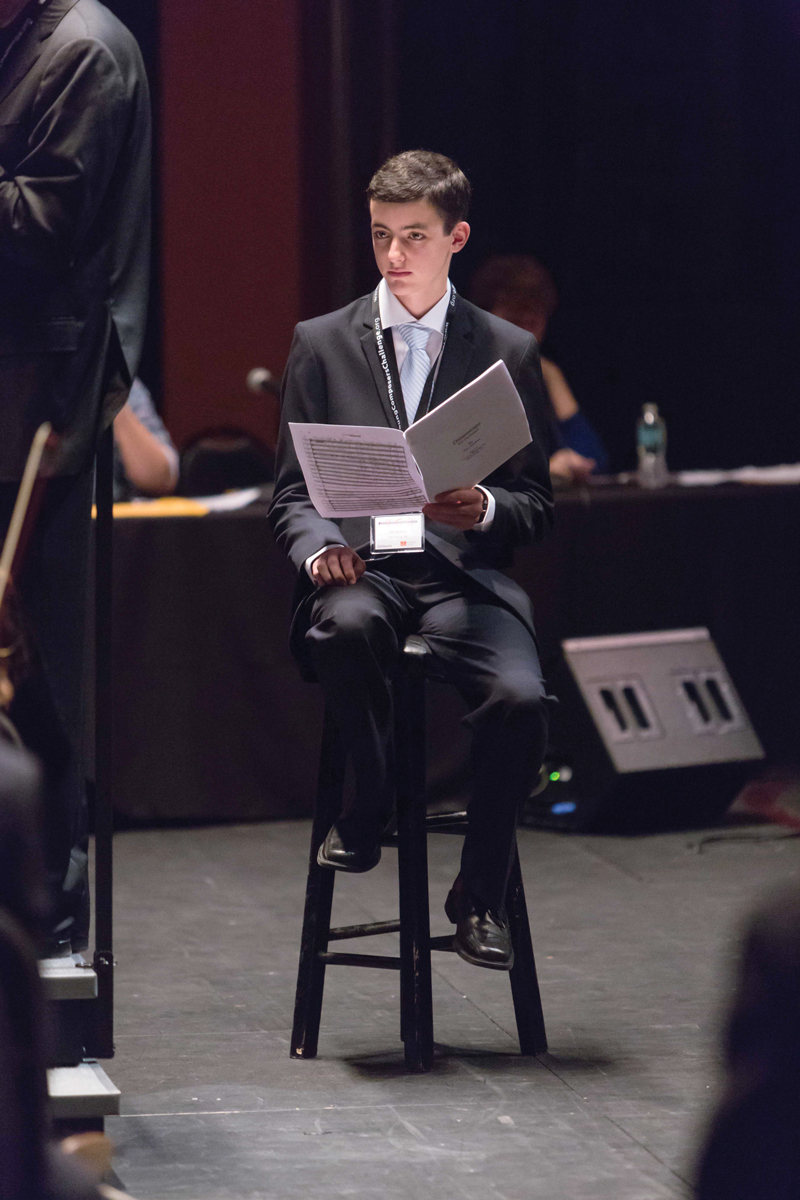

Like the other winners, Collins, a gangly, bespectacled youth with a wild nimbus of reddish hair, sat on stage in front of the orchestra as his composition was rehearsed, bit by bit, and then played all the way through.

Perched on a tall stool just a bow’s length from the cellos, Collins called to mind a child in the middle of a thrumming model-train layout as he swiveled his head — sometimes literally elevating off his seat — to watch his melody wind its way through the sections of the orchestra.

Up until that moment, like most other winners, he had heard the composition only in his head, or as played by a MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface), which uses a sound-sample library to approximate various instruments. The MIDI’s tinny, music-box tones are, to a full-fledged orchestral rendition, as a pineapple Life Saver is to the fruit off the tree.

But then, flesh-and-blood musicians have their own limitations. Breathing, for example. Young composers — natives of a digital, video-game universe — don’t always take that fact into account.

NYCC winners occasionally request Olympic-level gymnastics from the string section, or appear to presume that wind-instrument players have dirigibles for lungs. “We can cheat a little, but not that much,” advised a smiling, slightly breathless tuba player in mid-rehearsal.

Other young-composer misadventures include the occasional idiosyncratic twist on musical notation — those traditional, “expressive” scoring asides such as allegro, andante and largo that are meant to give players a sense of tempo, volume and overall mood.

This year, 17-year-old winner Elise Arancio, from Tucker, Georgia, submitted an ethereal ensemble piece called Kuma Lisa, the name of a mischievous fox in a Bulgarian folk tale whose personality she hoped to evoke. Members of the UCF chamber ensemble tasked with playing Kuma Lisa were charmed by Arancio’s ability to create a wispy, fairy-tale atmosphere — and amused by her notations advising them to play “devilishly,” “cheekily,” “naively” and in a “snarky” fashion.

All of which begs the question: How does a 17-year-old from Tucker, Georgia, wind up being inspired by a Bulgarian folk tale?

Arancio’s mother, Anne, appeared to have wondered the same thing. From her seat a few rows away from the stage, she could only extend her palms and shrug. “I just have no idea,” she offered. “She reads a lot.”

Others in the audience could relate to such parental bewilderment. Stuart Malina, conductor of the Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Symphony Orchestra, was part of an entourage that had travelled to Orlando with another winner — his son, Zev, a slightly built youth who all but disappeared into a dark suit on stage.

Zev was 14 when he wrote his winning orchestral submission, Dreamscape. By then, he’d been composing for several years. His father’s first clue that his son could write music came when he heard a beautiful waltz being played on the piano in their home.

“Who wrote that?” the father asked.

“I did,” replied the son, as casually as if he’d just been crayoning.

Music’s ability to shelter and sooth the adolescent soul has played out among many NYCC contestants. Take 18-year-old Daniel Zarb-Cousin, a winner for the second consecutive year. His Fantasy for Orchestra was an homage to the modern romanticism of Gustav Mahler.

Zarb-Cousin is old enough to see why his self-guided progression through the canon of composers eventually led him to his favorite: the revolutionary Austrian composer Anton Bruckner.

“I had a lot of instability and chaos in my life,” he said, taking a break from a photo session with the winners in the arts center’s lobby. “I think that’s why I wound up idolizing Bruckner. He’s very ordered, very rigid. That’s why I’m drawn to him. I have a need for structure.”

By validating their efforts with a heady artistic adventure and cash prizes — which range from $500 each for chamber pieces and $1,000 each for orchestral pieces — the NYCC often marks a turning point for its participants.

Zarb-Cousin, for example, was admitted to the prestigious San Francisco Conservatory of Music partly because he listed the award on his resumé.

This year, the NYCC itself reached a turning point. The program has, up to now, depended almost entirely upon Goldman’s hands-on participation and funding through his charitable foundation. Such an undertaking isn’t cheap; Goldman estimates that hard costs topped $60,000 this year.

Fortunately, for the first time since the NYCC debuted in 2005, UCF emerged as a partner, covering roughly half that amount by providing the chamber ensemble, paying for the Phil’s appearance and arranging for use of the Walt Disney Theater at no cost to the program.

Because the arts center was built with the help of a state grant, UCF, as a state institution, has an annual allotment of free performance dates at the downtown Orlando venue. This year, the university donated one of those designated dates to the Composium.

The NYCC’s expenses would also be much higher were it not for key, unpaid volunteers who’ve been with Goldman from the beginning. Those volunteers include Wilkins, who not only serves as the Composium’s conductor but also acts as an insightful and amusing emcee.

Indeed, one of the subplots of this year’s event was an emotional reunion between Wilkins and the Phil, which he directed until 2014. He’s currently music director of the Akron Symphony Orchestra and the Boston Landmarks Orchestra.

Three other key volunteers work with Goldman as judges, listening to more than 100 submissions every year and sending a taped, detailed critique to each contestant: Dan Crozier, professor of theory and composition at Rollins College; Keith Lay, chair of Music Industry Studies at Full Sail University; and Jeff Rupert, director of Jazz Studies at UCF.

Adding another educational component to the NYCC, this year music departments at UCF, Rollins and Full Sail assigned their students to study the winning compositions, and to attend the Composium.

Goldman, 66, doesn’t plan on scaling back his commitment to the program he created anytime soon. But he’s hopeful that the blossoming partnership with UCF will ensure the NYCC’s continuance for decades to come.

That’s also the hope of Jeff Moore, dean of the College of Arts and Humanities at UCF. Moore is convinced that Orlando, with its already-diverse arts community, is poised to become a hotbed of musical composition.

He sees the university’s involvement with the NYCC as a major first step toward a future in which UCF — where there’s an up-and-coming music composition program — will become a steward of the program.

“This can be a great tool for recruitment to UCF,” said Goldman. “I can see it helping to bring top-level composition students to the university from all over the country. There’s no reason that can’t happen here. And it needs to go on without me, some day. These kids are a national resource. We need them.”

Goldman’s crusade is rooted in his own teenage years, when he was a student at Maitland Junior High School and Winter Park High School. He began composing music for a full orchestra — an activity that didn’t do much for his social standing.

“I was pretty much of a lone ranger,” he recalled.

Goldman went on to graduate from the University of Florida with a degree in physics. (While in Gainesville, he also played in a rock ‘n’ roll band during an era when a promising, long-haired guitarist named Tom Petty was also making the rounds of local rock venues.

After college, Goldman enjoyed a lucrative stint as a tech entrepreneur. The company he founded, Distributed Processing Technology, pioneered computer disk caching technology and what came to be called RAID: Redundant Array of Inexpensive Disks.

The world as we know it now revolves around such computer storage technology: People who understand how computers work — and what RAID and caching did to enhance them — have been known to ask Goldman for his autograph.

In 2000, Goldman sold Distributed Processing Technology so he could devote himself entirely to philanthropy, much as his parents did when they helped to fund construction of the Orlando Shakespeare Theater in Loch Haven Park, where one of the venues in the complex is named for them.

Apart from the NYCC, Goldman has designed and operated an internet-based science-education initiative: Why U. Through the nonprofit program, whimsical animated videos — written by Goldman and animated by Tampa-based artist Mark Rodriguez — augment STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and math) in the K-12 and college levels.

Why U offers free access to its videos through its website, whyu.org, and its YouTube channel. The offbeat-but-effective tutorials have been used by at least 8 million people worldwide.

“What I realized is, there’s a lot of attention in the educational system that goes out to kids that are struggling,” Goldman said. “And that’s important, no question. But no one was addressing the need at the other end of the spectrum with these high-functioning but isolated kids.”

That sentiment is shared by NYCC donor Alan Ginsburg, who was part of the Composium audience watching this season’s batch of musical miracles unfold.

Ginsburg, an Orlando real estate developer by vocation but a stand-up comedian at heart, knows a good performance when he sees one. During intermission, he strolled up to the apron of the stage to congratulate his friend and fellow philanthropist, for another successful year.

“It’s just great what he’s doing for all these geniuses,” Ginsburg said. “That one kid — how old is he? 14? When I was 14, I couldn’t even ride a bike.”