DIGITAL PORTRAITS BY CHIP WESTON

Meet the Inaugural Class of Citizens Who Made History.

Winter Park residents, from those who originally settled the area to those who recently relocated, have always been passionate about their community and involved in making it an even better place to live, work and raise families.

Throughout the city’s 128-year history, talented and resourceful people have stepped up and made a difference — some profoundly so. That’s why Winter Park Magazine’s editors thought it was time to launch a Winter Park Hall of Fame, which would recognize those whose impact has spanned generations.

As of now, the Winter Park Hall of Fame is a concept only, unaffiliated with any organization other than the magazine.

Hopefully, though, the idea will catch on, and eventually there’ll be a permanent display and a formal process for selecting inductees. In the meantime, this particular Hall of Fame, informal though it may be, will exist in the pages of Winter Park Magazine and online at winterparkmag.com.

Caveats aside, here’s how our Winter Park Hall of Fame came together. In selecting the inaugural class, Winter Park Magazine used scholarly papers, books by local historians and consultations with longtime residents familiar with Winter Park history.

Only those who were still living were automatically excluded from consideration. Otherwise, there were no restrictions — and plenty of contenders.

Several iconic Winter Parkers were obvious choices, and their inclusion was assured. Some were slightly less obvious, but equally worthy. Even so, there were dozens upon dozens of others who could easily have been chosen, assuring that there’ll be no shortage of worthy candidates in years to come.

In the magazine’s judgment, these people were essential Winter Parkers — people without whom the community might have become a very different sort of place.

So, until there’s an actual, official Hall of Fame, let’s use the following pages to salute the inaugural class.

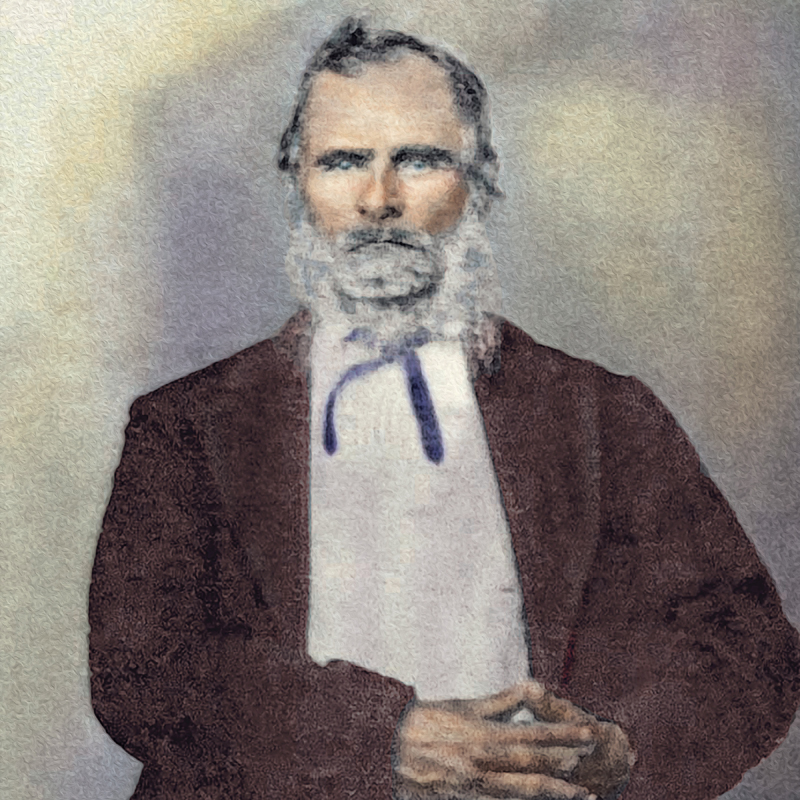

David Mizell Jr.

(1808-1884)

Homesteader –—————————

Mizell and his family moved to the area in 1858 from Alachua County, making them the first non-Native American residents in what was to become Winter Park. He built a cabin on a homestead between present-day lakes Osceola, Mizell, Berry and Virginia, and called the area Lake View (basically where the Genius Preserve and the Windsong subdivision are now). The Mizells grew cotton and raised horses, cattle, hogs, turkeys and goats. Mizell became politically influential, serving on the Orange County Commission and in the state Legislature. His eldest son, David W. Mizell, became the first sheriff of Orange County and was killed in the line of duty. Another son, John, became the first judge in Orange County and was elected to the first board of aldermen for the Town of Winter Park in 1887.

Wilson Phelps

(1821-Unknown)

Grower, Promoter –—————————

Phelps, a Chicago businessman-turned-citrus-grower who toured the area in 1874, purchased most of the land where the Mizells had lived and much more east of Lake Osceola. In addition to his citrus ventures, Phelps sold lots to fellow Chicagoans and played a key role in encouraging Loring Chase and Oliver Chapman to move forward when they sought his advice regarding the wisdom of turning the largely unsettled area into a posh winter resort. Phelps, acting as a one-man chamber of commerce, provided a strong letter of endorsement and all the data he could compile in a four-page, handwritten letter that is arguably the “big bang” of Winter Park’s creation. Certainly, it provided the basis for Chapman and Chase’s subsequent promotional materials. There is no known photograph of Phelps.

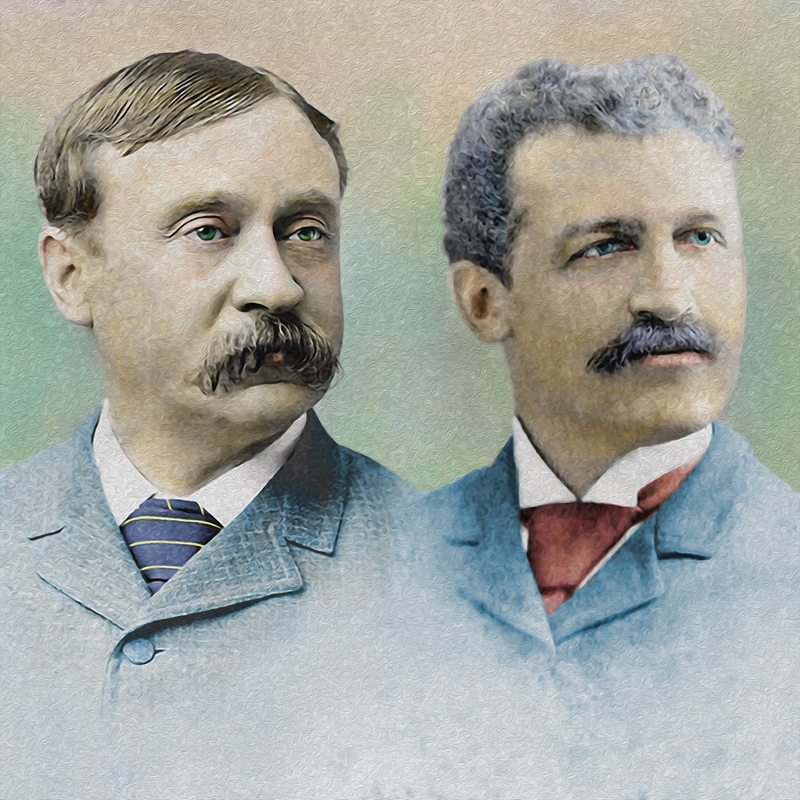

Loring A. Chase

(1839-1906)

Oliver Chapman

(1851-1936)

Developers –—————————

Chase, a real-estate broker from Chicago, moved to the area for his health in 1881. Enchanted by the lakes and woods, he believed he had found an ideal place to develop a winter resort catering to wealthy Northerners. He shared his idea with Chapman, a Massachusetts importer of luxury goods, and the two bought about 600 acres of what would become Winter Park. They commissioned a well-conceived town plan and soon began advertising heavily and selling lots to “Northern men of means.” In 1885 Chase bought out Chapman’s interest for $40,000 and the partnership was dissolved. Chapman, who feared his health was failing, returned to Massachusetts and enjoyed another 51 years of life, outlasting his former partner by decades. Although the Chase-Chapman team was short-lived, its significance is incalculable for Winter Park.

Edward P. Hooker

(1834-1904)

Clergyman; President, Rollins College –—————————

Hooker, a Congregationalist minister, came to Winter Park from Massachusetts in 1882 to oversee the establishment of a local church, now the First Congregational Church of Winter Park. Following Daytona Beach educator Lucy Cross’ 1884 challenge to the Florida Congregational Association proposing to build a college in the state, Hooker was asked to prepare a paper on the subject to be delivered at the association’s 1885 annual meeting. Hooker’s presentation was, according to contemporary accounts, stirring and effective. When the association decided that a college was indeed needed, Hooker, despite an obvious vested interest, was selected as one of five committee members receiving proposals from competing communities. When Winter Park was selected, Hooker was named Rollins College’s first president.

Lucy Cross

(1839-1927)

Educator –—————————

Cross had already founded the Daytona Institute for Young Women when she proposed that a liberal arts college be built in Florida “for the education of the South, in the South” at the 1884 meeting of the Florida Congregational Association. Her proposal, presented on her behalf by a minister from Daytona, was a major factor in the association’s decision in 1885 to hold a competition, and to build such an institution in the city offering the most generous inducements. Today Cross is known as “The Mother of Rollins College,” which is ironic since she pushed for a Daytona location. However, when the decision was made to choose Winter Park, Cross supported it strongly — and clearly deserves credit for bringing the issue of higher education in Florida to the forefront.

Alonzo W. Rollins

(1832-1887)

Industrialist, Benefactor –—————————

Rollins, a Chicago industrialist and seasonal resident of Winter Park, never attended college. But he was instrumental in founding one. He contributed $50,000 — a huge sum at the time — to the local effort to win a competition sponsored by the Florida Congregational Association, which had decided in 1885 that it would build a college somewhere in the state. That generous gift pushed Winter Park’s inducement to $114,180, far more than was offered by Jacksonville, Daytona, Mount Dora or Orange City. The institution, Rollins College, was named in its primary benefactor’s honor, although he died after attending only two meetings of the board of trustees.

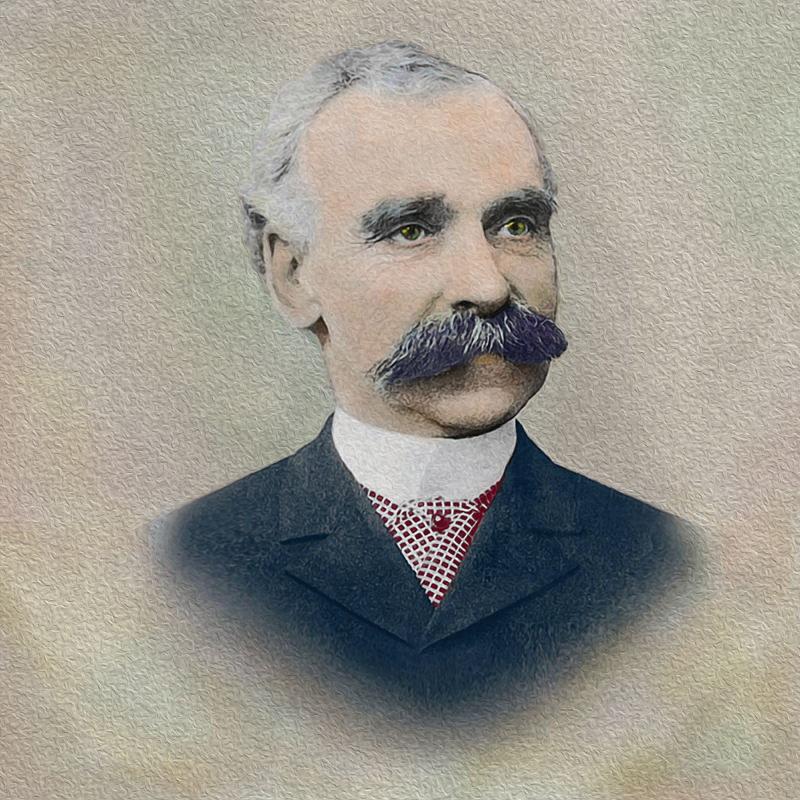

William C. Comstock

(1847-1924)

Civic Leader –—————————

Comstock, a grain merchant from Chicago, moved to the area in 1872 and 10 years later built a home, which he dubbed Eastbank, on the eastern shore of Lake Osceola, where Wilson Phelps’ home had stood. Today, Eastbank is the oldest home in Winter Park. A former president of the Chicago Board of Trade, Comstock encouraged other wealthy Chicagoans to join him in Central Florida. He was a director of the Winter Park Land Company and, in 1923, was elected first president of the newly organized Winter Park Chamber of Commerce. Comstock was involved in virtually every community cause, donating heavily to Rollins College and serving as a charter member of its board of trustees. Comstock’s enthusiasm and commitment, in fact, kept trustees from closing the college during hard times. Less laudably, in 1893 Comstock led a successful effort to de-annex Hannibal Square, populated exclusively by African-Americans. (The neighborhood was re-annexed in 1925, when the city changed its status from “town” (fewer than 300 registered voters) to “city” (more than 300 registered voters.)

Gus C. Henderson

(1865-1917)

Editor, Activist –—————————

Henderson, a charismatic African-American traveling salesman, moved from Lake City to Hannibal Square in 1886. He founded a printing company and, two years later, a weekly newspaper, the Winter Park Advocate. The Advocate, one of only two black-owned papers in the state, was read by both black and white residents. Henderson was also a politically active Republican, writing that “all we ever received came from the Republicans, and if that party never does any more special good for me, I shall die a Republican.” He quickly became involved in local issues and was a strong supporter of incorporation. In 1887, when an incorporation vote was scheduled at Ergood’s Hall, he rallied west side registered voters to violate curfew and attend. Without Henderson’s efforts, it’s no sure bet that incorporation would have passed, at least not then. And it’s a virtual certainty that if it had passed, Hannibal Square would not have been included in the town limits. Two years after incorporation, Henderson moved to Orlando where he published The Christian Recorder and later The Recorder.

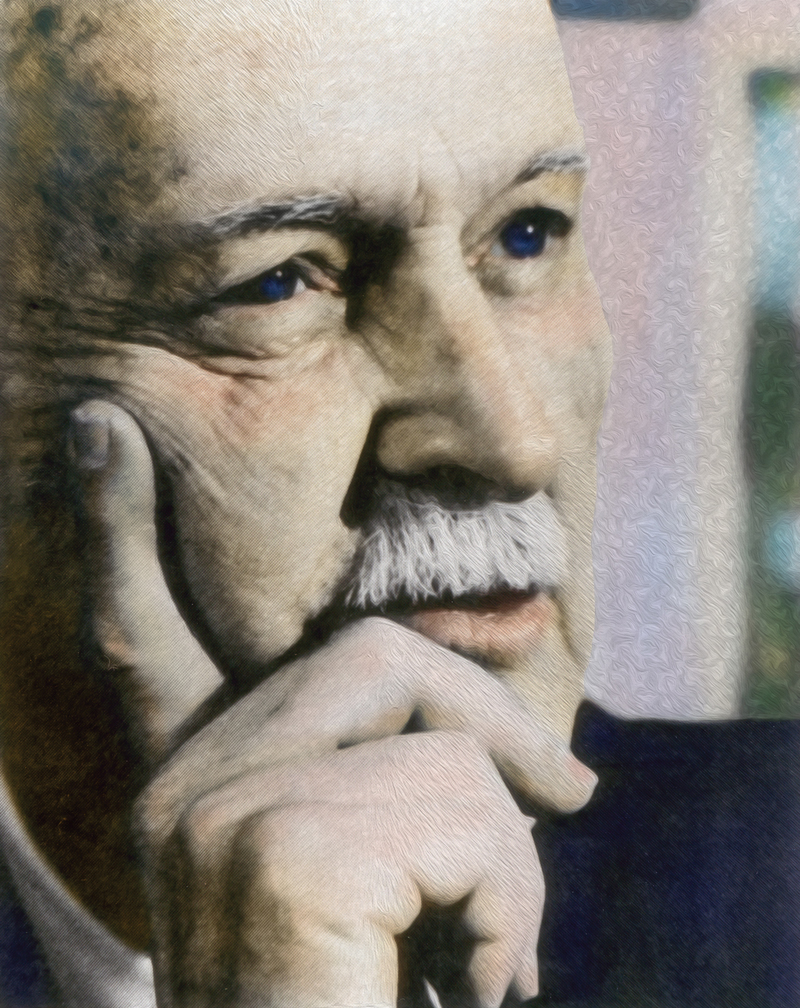

Hamilton Holt

(1872-1951)

President, Rollins College –—————————

Holt, previously a progressive journalist and social activist, arguably did more than any previous Rol-lins College president to shape the institution’s image and hone its mission. His innovative ideas on class-room learning were embodied in his “conference plan,” which eschewed traditional lectures in favor of one-on-one interaction between instructors and students. Holt’s innovative approach and personal charisma attracted a faculty of (sometimes quirky) academic superstars who, above all else, loved teaching. “I had no special qualification for the position,” recalled Holt, who came to the college after losing a U.S. Senate race in Connecticut. “But from observation in many colleges and from my own experiences, I had acquired definite ideas about teaching which I longed to put into practice.” In 1926 he created the Animated Magazine, a live program that hosted speakers ranging from actors to scientists to politicians. Three presidents of the United States — Calvin Coolidge, Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman — also spoke at Rollins at Holt’s behest. During Holt’s tenure, which lasted from 1925 to 1949, Rollins became a cultural center for musical and theatrical performances. In 1932, for example, he hired stage actress Annie Russell, for whom a new on-campus theater was built, to direct the drama department. The Rol-lins evening program, the Hamilton Holt School, is named in the legendary president’s honor.

James Gamble Rogers II

(1900-1990)

Architect –—————————

In a career spanning nearly 70 years, Rogers’ commercial, educational and residential designs enriched Winter Park’s distinctive aura of charm, culture and sophistication. Indeed, it could be argued that Rogers was as architecturally important to Winter Park as Addison Mizner was to Palm Beach and Frank Lloyd Wright was to Oak Park, Illinois. Stylistically, Rogers insisted that “architectural designs should be in harmony and should correlate with the general terrain and type of foliage that form the background for a town.” In Winter Park, he believed the subtropical environment lent itself to the kind of Spanish-style architecture that became his signature. But in addition to the large commissions for which he earned renown, Rogers also designed modest homes for businesspeople, artists and professors, demonstrating his ability to work within a restricted budget and still deliver a satisfying product. The highlight of Rogers’ final years of practice was the Mediterranean-style Olin Library at Rollins College, which he designed in 1985. Over the years, he was involved in the construction or the remodeling of more than 20 buildings on the Rollins campus. Today his remaining homes are prized by architecture aficionados. A prime example, Casa Feliz, was saved from the wrecking ball, moved and is now a community center and museum.

Hugh F. McKean

(1908-1995)

Educator, Artist, Philanthropist –—————————

Jeannette Genius McKean

(1909-1989)

Businesswoman, Artist, Philanthropist –—————————

Hugh and Jeannette McKean must surely be regarded as Winter Park’s first power couple. Hugh, artist, educator, collector and writer, was the 10th president of Rollins College, serving from 1951 through 1969. He then became the college’s chancellor and chairman of its board of trustees. In 1945, while still an art professor at the college, he married Jeannette Morse Genius, granddaughter of Charles Hosmer Morse, the Chicago industrialist and philanthropist who helped to shape modern Winter Park. In 1942, Jeannette built and donated the Morse Gallery of Art on the Rollins campus. Hugh became the gallery’s director, a position he held until his death, just months prior to the opening of the new Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, the facility’s spectacular showplace on Park Avenue North. The museum displays the world’s most important collection of Louis Comfort Tiffany’s works, many of which the McKeans salvaged from the artist’s ruined Long Island estate, Laurelton Hall. Hugh also served as trustee of the Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota and of the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation in New York. Jeannette, an acclaimed artist in her own right, was also a successful businesswoman, working as an interior designer, owning and operating the Center Street Gallery on Park Avenue and managing her grandfather’s properties as president of the Winter Park Land Company. Both McKeans were lovers of nature, and cultivated a preserve filled with peacocks around Wind Song, the lakefront estate built by Jeannette’s father, Richard Genius. (Her mother, Elizabeth Morse Genius, died in 1928.) Genius Drive, the dirt road leading through the preserve and to the estate, was open to the public until the 1990s. The property, now known as the Genius Preserve and owned by the Elizabeth Morse Genius Foundation, is part of a restoration project by the Department of Environmental Studies at Rollins. It includes the largest remaining orange grove within Winter Park and several structures, including the estate. Jeannette was named Winter Park’s Citizen of the Year in 1987, while Hugh was posthumously named the Orlando Sentinel’s Floridian of the Year in 1996.

John M. Tiedtke

(1907-2004)

Businessman, Philanthropist –—————————

Tiedtke played a little piano, but mostly he enjoyed listening to classical music, performed live. Thanks to him, thousands of other Central Floridians can do the same. He was a founding member of the Florida Symphony Orchestra, which played its last note in 1993. But Tiedtke’s most lasting legacy is the world-renowned Bach Festival Society of Winter Park. The organization’s viability was in doubt before Tiedtke — at the behest of boyhood friend Hugh McK-ean — assumed control in 1950. It not only survived but thrived, thanks in large part to Tiedtke’s 45 years of hands-on leadership and generous financial support. Tiedtke, who made his fortune cultivating sugar in the Florida Everglades, was a professor, treasurer, second vice president and dean of graduate programs at Rollins College before becoming a member of the institution’s board of trustees. In 2003, on his 96th birthday, Rollins established the John M. Tiedtke Endowed Chair of Music. Later, the John M. Tiedtke Concert Hall was named in his memory. Although Tiedtke’s legacy is strongly associated with the Bach Festival and Rollins, he also funded Maitland’s Enzian Theater “to inspire, educate, and connect the community through film.” Elizabeth Tiedtke Mukherjee, his granddaughter, still serves as Enzian’s executive vice president.

A DREAMER AND A DOER

UNSUNG HERO AWARD

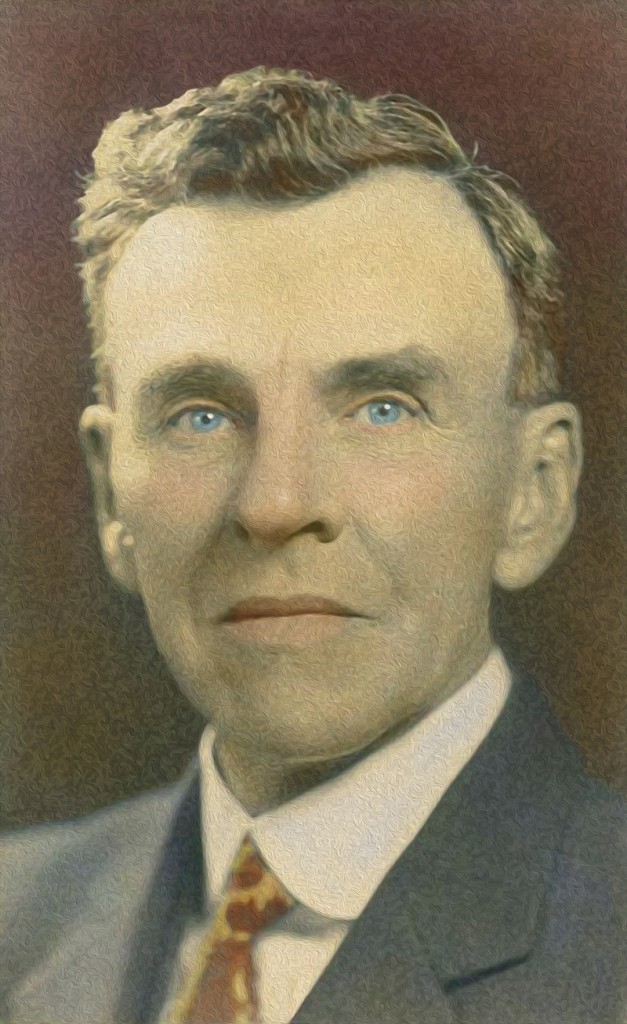

Edwin Osgood Grover

(1870-1965)

Professor, Civic Activist –—————————

Edwin Osgood Grover is barely remembered today. There is one small street named for him — Grover Avenue, appropriately near Mead Garden — and a commemorative stone along the Rollins College Walk of Fame.

But he’s ubiquitous in Winter Park history as a dreamer and a doer; a writer and a poet who frequently descended from his ivory tower to make a practical difference in the community. Surely his most enduring gift was his pivotal role in the founding of Mead Garden, an extraordinary 48-acre urban oasis unlike anywhere else in Central Florida.

Grover was born in Minnesota in 1870, but was raised in Maine and New Hampshire, where he wandered in the thick woods and developed a love for nature.

While attending Dartmouth College he worked as a reporter for the Boston Globe and edited the Dartmouth Literary Monthly. After graduating in 1894 with a degree in literature, he enrolled in graduate school at Harvard. However, instead of earning an advanced degree he chose to visit Europe and the Middle East — an adventure he managed despite having only $300 to his name.

Upon his return to the U.S. in 1900, Grover worked as a textbook salesman in the Midwest and shortly thereafter became chief editor of Rand McNally in Chicago. He formed his own publishing company in 1906, but sold his interest six years later and became president of the Prang Company, a manufacturer of crayons and watercolors.

After “serving a sentence of [almost] 30 years in the publishing business,” Grover was ready to retire. Then, in 1926, a call from Rollins President Hamilton Holt prompted a change of plans. Holt wanted Grover as the college’s “professor of books,” making him the first academic in the U.S. to hold such a title. Intrigued, he accepted.

At Rollins, Grover helped students publish the college’s first literary magazine, Flamingo, in 1927, and for the next two decades was “editor” of the Animated Magazine, which was not a published work but a series of lectures featuring national figures from politics, literature, the arts and even show business.

Grover was also a charter member of the University Club of Winter Park and helped found Winter Park’s first bookstore, The Bookery. He encouraged his wife, Mertie, to spearhead the opening of a day nursery for the children of African-American working mothers. The Welbourne Day Nursery is still in operation today.

When Mertie was killed in an automobile accident, Grover asked that funds in her name be donated for the establishment of a children’s library on the predominantly black west side. The Hannibal Square Library operated until 1979. He also raised money for the DePugh Nursing Home, now the Gardens at DePugh.

His biggest project, however, was Mead Garden. He didn’t donate the land, but through sheer force of will and dogged determination, he got it donated. And through ingenuity and persuasiveness, he got the massive undertaking organized and funded

A man of varied interests, Grover was a friend of Oviedo-based horticulturist Theodore L. Mead and a follower of Mead’s work. Coincidentally, one of Grover’s students at Rollins was John “Jack” Connery, who had been a Boy Scout in a troop led by Mead. While attending college, Connery had continued to assist his aging former scoutmaster, who was best known for his pioneering work on the growing and cross-breeding of orchids.

Upon Mead’s death in 1936, Connery inherited his grateful mentor’s collection of amaryllis, hemerocallis, fancy-leaf caladiums and more than 1,000 orchids. Mead’s young protégé had been a student curator of the Rollins Museum of Natural History, so he knew horticulture. And he had been faithfully caring for the plants at Mead’s now-unoccupied estate.

Connery knew, however, that a more permanent solution was needed if the collection was to be saved. He and Grover hoped to establish some sort of memorial garden that would pay homage to a man they both admired while providing students a place to study plants and nature.

But where? Grover had considered pushing Rollins to buy Mead’s Oviedo property. Connery, however, thought he had a better idea. Would Grover be willing to join him for an expedition?

The duo explored the untamed site of what would become Mead Garden. Excited by the possibilities, they hurried to the office of real-estate developer Walter Rose, who owned 20 acres buffering his subdivision, Beverly Shores. After hearing out Grover and Connery, Rose agreed to donate his property to the city.

James A. Treat, a former Winter Park mayor, gave another six acres that included an egret rookery and a heretofore hidden lake that Grover and Connery had discovered. The diplomatic Grover promptly named it “Lake Lillian,” for one of Treat’s granddaughters.

R.F. Leedy, a Park Avenue clothing merchant, was persuaded to kick in a tract bordering Pennsylvania Avenue, and a Jacksonville woman, Mary Bartell, turned over 20 acres of high ground where today’s entrance greets visitors.

Orange County owned a quarter-acre encompassing a clay pit. But the county agreed to give it up, and the clay was eventually used to bolster the garden’s meandering nature trails.

On May 11, 1937, Theodore L. Mead Botanical Garden Inc., a nonprofit organization that would operate the garden, was formed. At its helm were Grover as president and Holt as honorary president. Connery was named director and executive secretary.

Mead Garden officially opened on Jan. 15, 1940, in a formal ceremony that included local dignitaries and elected officials. Grover, who presided over the proceedings, laid out a grand vision of a garden encompassing unspoiled natural areas, greenhouses for exotic plants and even aquariums, which were never built.

Today Mead Garden, owned by the city and maintained by the Friends of Mead Botanical Garden Inc., remains an ecological jewel, and is undergoing a major renovation and restoration.

Tucked away at the end of South Denning Drive, across the railroad tracks and bounded by Pennsylvania Avenue and Howell Creek, it has enchanted casual visitors and serious naturalists for decades. Few know that a professor of books is largely to thank.

HIS KIND OF TOWN

Citizen of the Century

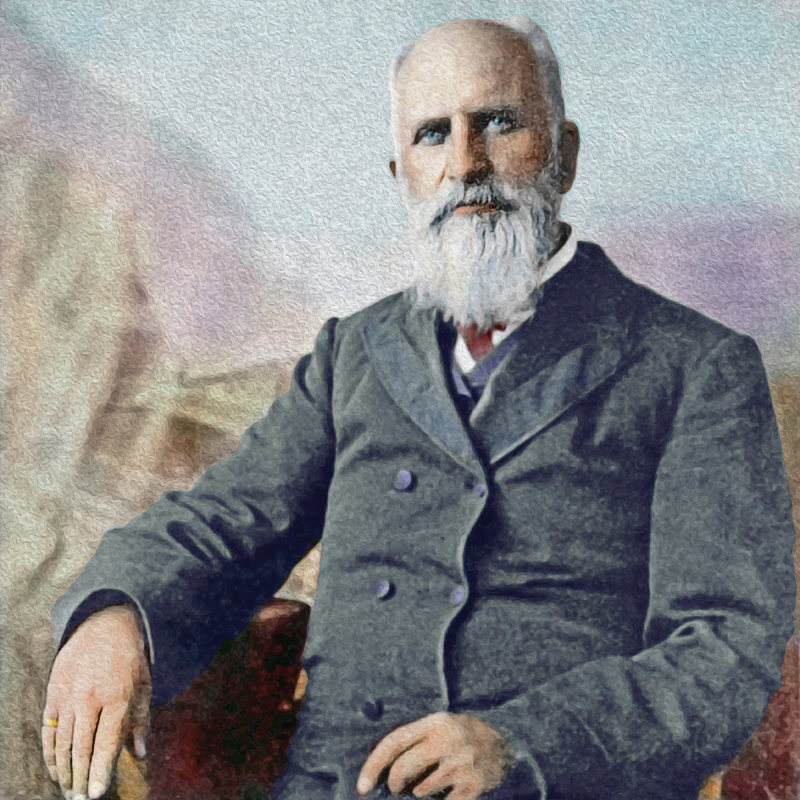

Charles H. Morse

(1833-1921)

Industrialist, Philanthropist –—————————

Charles Hosmer Morse was a very wealthy man. Luckily for Winter Park, he was also a very enlightened and generous man. In 1904, the Chicago-based industrialist bought nearly half the city’s acreage. He then began developing his holdings with the goal of creating a sophisticated and vibrant community of well-to-do kindred spirits.

In so doing, Morse, more than any other individual, shaped modern Winter Park. Although he grew even wealthier in the process, Morse believed that enhancing the community in which he had wintered since the 1880s was more important than profiting from it.

Like many early Winter Parkers, Morse originally hailed from New England. Born in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, he graduated from St. Johnsbury Academy in 1850 before joining his uncle, Zelotus Hosmer, as an apprentice in the Boston office of E. & T. Fairbanks Co., a manufacturer of weighing scales. His salary was $50 per year — approximately $1,500 today.

(Winter Park’s Fairbanks Avenue is named for Franklin Fairbanks, whose father, Erastus, and uncle, Thaddeus, founded E. & T. Fairbanks in 1824. Franklin also worked in the family business and, in 1888, became its president. He shared Morse’s enthusiasm for Winter Park, and joined his friend as both a seasonal resident and a property owner with a vested interest in seeing the city thrive.)

Morse worked his way up the ladder at E. & T. Fairbanks. In 1855 he was transferred to New York as a clerk and salesman. Two years later he was sent to help establish an affiliate company, Fairbanks & Greenleaf, in Chicago. In 1866 he founded Fairbanks, Morse & Co., which manufactured windmills, pumps, locomotives and other industrial equipment. (Fairbanks, Morse & Co. bought controlling interest in E. & T. Fairbanks in 1916.)

A titan in the Windy City’s business community, Morse became a multimillionaire during the Industrial Revolution that followed the Civil War — a time when a cadre of magnates with names like Rockefeller, Vanderbilt, Carnegie and Morgan amassed great fortunes.

Although the white-bearded Morse certainly looked the part of a Gilded Age tycoon, he wasn’t in that rarified league financially. Still, he was among the richest men in the country at a time when all the millionaires combined totaled only several thousand. He felt comfortable in sleepy Winter Park, where many upper-crust Yankees sought refuge during the snowy months.

Ironically, cold weather — brutally cold weather — triggered a series of events that put the city’s fate in Morse’s hands. In a region that was supposed to be below the frost line, two back-to-back freezes — in December of 1894 and February of 1895 — brought temperatures that set historic lows.

Sap froze inside tree trunks, splitting many of them open with pops sounding like gunshots. The first freeze was damaging but the second was ruinous, wiping out citrus groves and devastating the local economy.

The Winter Park Company, the city’s primary land developer, felt the sting. It defaulted on loan payments to the estate of Francis Bangs Knowles, who had been the company’s largest shareholder, and surrendered roughly 1,200 lots to satisfy the debt. Adding insult to injury, the posh Seminole Hotel, where Morse typically wintered, burned to the ground in 1902.

Morse, while certainly distressed over the misfortune that had befallen his local friends, also recognized a dual opportunity. He could make a savvy investment while ensuring that the city he had come to love — and to which he planned to retire — would remain a congenial and cultured place.

In 1904 Morse bought the Knowles estate’s vast holdings for roughly $10,000 — the equivalent of about $250,000 today. That fateful transaction was colorfully recalled by Harold A. “H. A.” Ward at a 1954 dinner commemorating his retirement from the Winter Park Land Company, which was formed by Morse to purchase the Knowles properties.

Ward was working at the Pioneer Store, located at the corner of Park Avenue and The Boulevard (later Morse Boulevard), a general-merchandise emporium that also sold real estate. Here’s how Ward told the story of perhaps the most important business deal in Winter Park’s history:

“Well, as I had said, Mr. Morse came into the store and asked if I had the sale of the Knowles estate property. I said. ‘That’s correct. Would you like to buy a lot?’ And we talked a little, and he said, ‘What’ll they take for the whole shebang?’ That’s the way he expressed it. It like to have knocked me down.”

Ward “blurted out the low price they’d given me” and Morse said he’d take it — with one condition: “Provided you can get released from your present work here, and take charge of the property for me.”

After all, Morse noted, his primary home was still in Chicago, and he’d need year-round local management. So Morse — along with his son, Charles H. Morse Jr. (who lived full time in Chicago) and Ward — became the original directors of the newly formed Winter Park Land Company. (Ward’s grandson, Harold Ward III, is today a prominent Winter Park attorney.)

In addition to property owned by the Knowles estate, Morse acquired about 200 acres of heavily wooded land bordered by lakes Virginia, Mizell and Berry. There he planted orange trees and later carved out an unpaved road, Genius Drive, which decades later would become one of Winter Park’s most cherished attractions, thanks to its profusion of peacocks.

Morse then remodeled a home at the corner of Interlachen and Lincoln avenues for use as his winter residence. Osceola Lodge was transformed into a textbook example of Craftsman-style architecture and filled with custom Mission-style oak furniture, walls of books and an array of rustic Indian artifacts.

From this cozy and comforting setting, Morse supervised development of his properties and quietly — sometimes anonymously — supported community causes.

(Osceola Lodge still stands, and is today headquarters for the Winter Park Institute, a Rollins College-affiliated organization that sponsors seminars, lectures, readings, classes and discussions with prominent scholars and thought leaders in an array of fields.)

In 1906 Morse deeded land that became Central Park to the city, but only so long as it was open to the public and not developed. He helped form the Winter Park Country Club, serving as its first president and providing the land on which the clubhouse and golf course were built. He asked the versatile Ward to design the course, along with a golf pro named Dow George. (The facilities, now owned and operated by the city, are still in use today.)

Morse, who retired and moved to Winter Park permanently in 1915, also donated the Interlachen Avenue site on which the Woman’s Club of Winter Park built its headquarters. He paid for construction of a city hall in 1916, and for years routinely covered operating deficits at Rollins as a member of the college’s board of trustees.

He paved roads, funded a citrus packing house, gave property to churches and even provided startup capital for construction of a second Seminole Hotel.

He also personally selected who could buy lots. He refused to sell to investors, for example, explaining in no uncertain terms that he’d do the speculating in Winter Park. Only people who planned to build homes could buy lots. And, of course, the homes to be built had to be of acceptable quality.

Morse recruited potential residents whom he admired, among them novelist Irving Bacheller. (Eben Holden: A Tale of the North Country and D’ri and I had been among his bestsellers.) “Now, Mr. Ward, I’ve got to get Irving Bacheller to come down here,” he told his manager in 1918. “He’ll be a great asset to Winter Park. I want you to be sure to land him here, no matter what you have to do.”

Bacheller, though, drove a hard bargain. Morse ended up taking the author’s Connecticut farm in trade and loaning him the money to buy a large lakefront tract on the Isle of Sicily, where he built a handsome Asian-style home he dubbed Gate O’ the Isles. “I think Irving Bacheller missed his calling,” Morse grumbled to Ward. “He should have been a horse trader.”

But Bacheller did, indeed, prove to be a great asset — in ways that Morse couldn’t have predicted. In 1925, as chairman of the search committee for a new Rollins president, he pursued a progressive New York magazine editor who had published his poetry. At the author’s behest, Hamilton Holt took the job — and turned Rollins into a nationally acclaimed institution.

Morse died in 1921, at Osceola Lodge, secure in the knowledge that his investment had been a wise one in every way possible. His second wife, Helen Hart Piffard, remained in the home until her death in 1929. (His first wife, Martha Jeannette, had died in 1910.)

In 1937 Morse’s son-in-law, Richard Genius, built a vacation home on the Genius Drive property. It was first dubbed Casa Genius, but later renamed Wind Song. (Genius’ wife and Morse’s daughter, Elizabeth Morse Genius, died in 1928.) Jeannette Genius McKean, daughter of Richard and Elizabeth, moved there with her husband, Hugh, in 1951.

The McKeans brought with them the now-iconic peacocks, the descendants of which still noisily preen around the estate and the adjoining neighborhood.

Today the Morse name is on Morse Boulevard and the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, which was founded by Jeannette and Hugh. It wasn’t until 1986 that a memorial was erected in Central Park commemorating Morse’s contributions to the city he was instrumental in shaping.

The two-sided brick structure, designed by legendary architect James Gamble Rogers II, is impressive. But Morse, “the most modest man I ever knew,” according to Ward, would undoubtedly have considered the thriving, culturally rich city that Winter Park has become to be the only monument to his memory that really mattered.

Editor’s Note: Original black-and-white photography in this story is courtesy of the Rollins College Archives and Special Collections at the Cornell Library.